What is Psychological Safety?

Amy Edmonson starts her book ‘The Fearless Organisation’ with the quote by Edmund Burke: “No passion so effectively robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear” (1756). A ‘fearless’ or psychologically safe organisation may conjure up an image of a brave or even reckless organisation, but for Edmonson, it is one where fear is driven out ‘to create the conditions for learning, innovation and growth’. Fear stifles individuals’ contributions, it creates barriers and it results in energy being diverted from what is most important to an organisation and its people to what are essentially unproductive feelings and behaviours (impression management and face-saving behaviours for example).

Psychologically safe work environments have been proven to lead to greater innovation, better team learning, higher quality outputs, better employee engagement, and wellness as well as delivering better results. Through this article, we will outline the background of psychological safety and how to improve it.

The background of Psychological Safety

Professor Amy Edmonson from Harvard Business School is mostly known for her impressive research on psychological safety, but she is clear that this all started before her. This is true, however, her work coupled with a research project by Google (Project Aristotle) has brought the term into common parlance and made it a focus of positive attention. Research on the topic appears to have started back in 1965 with Bennis and Schein, followed by Demming in 1982 and Kahn in the 1990s. Amy Edmonson’s now famous paper on Psychological Safety and Learning Behaviour in Work Teams (1999) followed although it remained somewhat dormant until 2016 when a New York Times article caused it to enter mainstream conversation. Essentially, through this article, Google shared the output of a comprehensive internal research project (code-named ‘Project Aristotle’) to understand why some teams thrived and some did not. They described how when they encountered the concept of ‘psychological safety’, everything fell into place. Their research concluded that whilst other things matter (e.g. clear goals, culture of dependability, etc), psychological safety more than anything else was the key factor in making a team work. Edmonson’s work has now become broadly recognised, with her original work cited more than 11,000 times in academic papers.

Why is Psychological Safety important?

In Prof Edmonson’s recent book ‘The Fearless Organisation’. She describes psychological safety ‘not as a perk’ but as ‘essential to producing high performance in a VUCA world’. She describes how positive benefits have been evidenced for learning, engagement and performance in a wide range of organisations. More than ever before, when expertise alone is insufficient to solve the complexities we face, we need to create environments where we can hear different voices and perspectives on the problems we face. This can only happen where we are working in psychologically safe environments.

The Benefits

A psychologically safe environment does not guarantee team effectiveness, rather it is a foundation, but without it teams are unlikely to succeed in the long-term. There are many benefits to psychological safety, but Amy Edmonson quotes specific research which illustrates the links between psychological safety and learning, engagement and team performance.

Learning:

In Edmonson’s original paper (1999), she describes learning behaviours in groups such as seeking feedback, sharing information, asking for help, talking about errors with other team members and experimenting. It is through these activities that teams can learn and deal with issues as they arise, stay in touch with customer needs, respond to changes in their environment collectively and collaboratively. Each of those activities however has an interpersonal dimension that cannot be underestimated and it has been proven that many of us engage in face-saving activities which affect our willingness to engage in such an open manner. Professor Bob Kegan and Susan Lahey of Harvard University talk about how many of us go to work doing two jobs, the job we were hired to do and the job of protecting our image. Are you brave enough in your organisation to share a half-baked idea? A half-baked idea explored with colleagues could become the next great innovation for an organisation. Where psychological safety is not present, creative ideas will be stifled. Where team psychological safety at work is present, team members feel safe taking interpersonal risk and they are freed up make valuable contributions and to work together in an open way, learning together and focusing on the work they are engaged in, without the distractions or fears of personal consequences for individual members. Psychological safety does not mean that learning will take place, but it creates the conditions for it to take place. It enables people to contribute what they know (good or bad), ensuring a broader perspective on challenges faced and influencing everyday decisions.

Engagement:

We can imagine if we take this thinking forward, how employees feel more engaged in psychologically safe teams, where there is open exchange of information, concerns and ideas and this in turn will improve team effectiveness. Gallup, an international organisation which advises on employee engagement, was able to prove meaningful improvement in engagement scores in an environment where psychologically safe principles were implemented. At a time of ‘quiet quitting’ and high employee turnover, this is an useful lever to impact positively on engagement.

Performance:

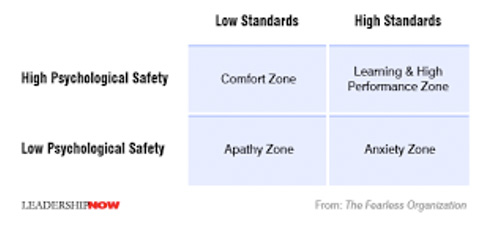

Psychological safety at work on its own won’t be sufficient however to achieve high team performance. Edmonson maps performance standards and psychological safety in the chart below and whilst having high psychological safety is a good thing, without high standards there may not be a compelling reason to learn or innovate which will in turn impact fulfilment, engagement and performance. The sweet spot is the ‘Learning and High Performance’ zone.

Some examples:

Edmonson describes many case studies of organisations or work units where low psychological led to catastrophic failures, including the well-documented case of the space shuttle Columbia. She also documents positive success stories including organisations such as Pixar which actively build psychological safety at work, so healthy feedback can enhance the creative process. Its most notable success using this process was Toy Story 2, which was successfully diverted from a road to failure through their ’Braintrust’ process. Google’s research, which ultimately advocated psychological safety as a path to high performing teams, included analysing one hundred and eighty teams for over a year. All of these examples lead me to wonder why more organisations are not pursuing this approach? Perhaps the gap is knowing where to start.

The Four Stages of Psychological Safety:

In Dr. Timothy Clark’s book ‘The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety’ (2020), he outlines key stages in the development of psychological safety: (1) Inclusion safety; (2) Learner safety; (3) Contributor safety; (4) Challenger safety. The starting point for a team leader is ensuring that everyone on a team feels included (inclusion safety). If team members don’t feel included, they are unlikely to expose areas of weakness, are less likely to learn and certainly will not feel comfortable contributing to the group or challenging the status quo. If we have an inclusive environment, the next step is creating psychological safety for team learning (learner safety), an environment where making mistakes are openly disclosed and learned from. If mistakes lead to personal consequences, communication will start to shut down and we are less likely to hear of problems, opportunities for learning are lost and ultimately work quality will be impacted. The next stage is contributor safety. In such an environment, team members listen to others, they are open to new ideas and the environment feels collaborative rather than authoritative. Building then on contributor safety, we want to get to the point where team members feel that they can constructively challenge the status quo (challenger safety), irrespective of their level, that there are no sacred cows that can go unchallenged and that ultimately it is about the team focusing on the best way of achieving their purpose and goals whilst being respectful, but without pandering or being fearful of the response.

Timothy Clarke uses the great phrase ‘Cover for Candour’ to describe how team leaders must provide air cover so that candour can be safe. As you can gather from this, a psychologically safe workplace isn’t a cosy environment. It is an honest and candid environment where frank exchange is possible and less time is spent on impression management.

How to develop psychological safety

In order to achieve ‘ Cover for Candour’, Amy Edmonson suggests that team leaders cultivate the following three behaviours: (1) Setting the Stage; (2) Inviting engagement and (3) Responding Productively. When reading this, it is worth considering the merit of including these in all leadership development initiatives in your organisation.

Setting the stage:

Whether you are launching a project or opening a team meeting, it is helpful to consider ‘setting the stage’ at this early point to cultivate an environment of openness and candour. This consists of two parts: emphasising purpose and consciously framing the narrative around failures. Questions to explore could include: What is the mission of this team?; Why is its work important?; How much uncertainty is being faced?; To what extent is the work complex and interdependent?; What are the implications of failure?; What is the tolerance for failure? Tolerance of failure will vary depending on the context. In a medical or airline context for example, failure may be life-threatening, whereas in an administrative environment it is highly unlikely. In either case, however, we want mistakes to be disclosed and candour to be encouraged. Framing the narrative around failure will enable the team to understand the stakes and create a sense of common purpose.

Inviting Engagement

Now, we need to actively encourage engagement. Amy Edmonson speaks of how hard it is to build psychological safety at work, but how easy and quick it can be to destroy. It is built on trust and engagement, which we need to constantly work on. If we truly want to invite engagement, then two practices can be particularly helpful: situational humility and proactive enquiry.

Humility is the recognition that we don’t have all the answers, to be aware of our own fallibility. When it applies to a particular situation, it can be more easily adopted as a mind-set by those in charge (‘situational humility’). Research by Mitchell, Johnson and Owens (2013) has shown that teams engage in more learning behaviour when those in charge express humility.

This links very nicely with the next practice, that of proactive enquiry. Edmonson describes it as ‘purposeful probing to learn more about an issue, situation, or person’. We can interpret that as to practice active listening, but I personally prefer Jennifer Garvey Berger’s term ‘listening to learn’. She distinguishes between ‘listening to win’, ‘listening to fix’ and ‘listening to learn’. Listening to learn is a wonderful and important skill to truly understand and appreciate another person’s perspective. This short video clip (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zrg_3KlAE6o) is well worth a watch to learn more about this. We can even catch ourselves in the moment listening to win or to fix and take a pause, shift gear and choose active listening and watch our body language. In doing that, we send a signal to our team that they are important and what they are saying is important and we invite their input.

Responding Productively

People take risks when they share their concerns, mistakes or give their input. Leaders who welcome only good news may unwittingly miss out on early signs that there are problems.

People take risks when they share their concerns, mistakes or give their input. Leaders who welcome only good news may unwittingly miss out on early signs that there are problems.

This step is about ensuring that we respond in a productive fashion and with emotional intelligence to the interpersonal risks people take in providing input. Our ability to demonstrate both self awareness and self regulation in managing our responses are equally important, thereby enhancing employees experiences of providing feedback.

In addition, if we can role model such behaviour, team members are more likely to raise issues or concerns in the future and themselves promote psychological safety. Edmonson describes how such responses have three key elements: (1) expressions of appreciation; (2) destigmatising failure and (3) sanctioning clear violations.

How do we know if an environment is psychologically safe?

To be honest, the answer to this is instinctive. Individual members of the team will gauge how safe they feel and this will influence their behaviour. As a team leader, we should watch out for these indicators: do people feel comfortable expressing their concerns?; does bad news travels fast enabling learning and corrective action? Do teams openly work together to solve problems? Is CYA behaviour non-existent?

Equally, there is a simple 7-question survey to measure psychological safety. This is called the Psychological Safety Scan and do get in touch if you want to hear more.

Some Useful Principles to summarise:

Firstly, psychological safety is not something that gets achieved and we move onto the next initiative. It is hard to cultivate and maintain psychological safety and it can be easily destroyed. It involves a set of practices that need to be constantly worked on all the time building psychological safety. Secondly, psychological safety isn’t just part of the company’s culture, it sits at group level, so whilst a CEO may desire to create a psychologically safe work environment, it is the behaviours at the group level that will determine the reality. It is entirely likely that in organisations psychological safety will be there to varying degrees across different teams with some having higher psychological safety. Efforts to achieve greater psychological safety need to led at work-group or team level and should form a central part of all leadership development initiatives. Finally, psychological safety is not the end goal, it is an enabler for organisations to achieve their goals – that’s the point of it.

Recent Comments